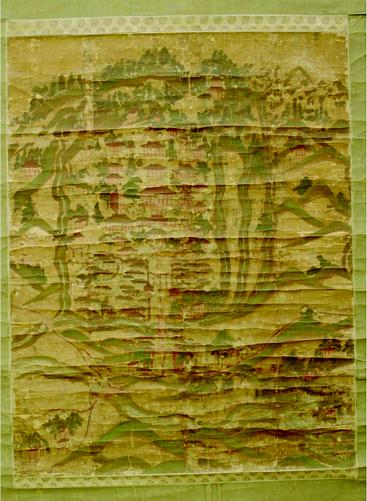

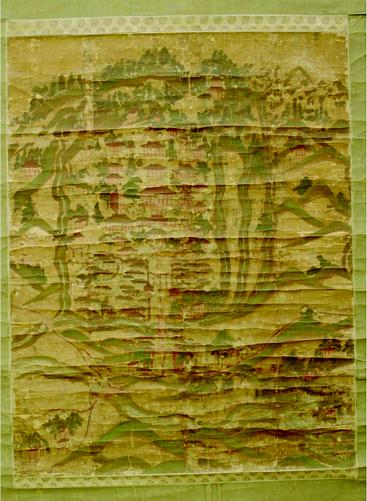

This painting depicts the Buddhist temple Enichiji in the Aizu region. It takes the form of a map, with the north direction at the top. In addition to the Enichiji complex proper, the painting depicts the temple's surroundings and a few of its more distant holdings.

The painting shows some ninety structures and archaeological remains of various types. A path leads into the temple from south to north, across a pair of streams and beneath two torii (Shinto-style gates). The buildings clustered on either side of the path appear to be dwellings, perhaps a small-scale version of the monzenmachi (temple gate towns) that grew up around religious institutions in the medieval age.

The path enters the temple complex through a three-bay wide gate which probably contained images of the Niō (Two Deva Kings) that often function as temple guardians. The Central Gate comes next; it is a more substantial building, seven bays wide. A outdoor stage separates the gates from the Golden Hall, which housed the temple's main images; according to temple tradition, these were statues of Yakushi Buddha and the bodhisattvas Nikkō and Gakkō. We do not know the function of the small Konpondō ("Origin" Hall) behind the Golden Hall; the Two Worlds Hall (Ryōkaidō) behind it may have been used to display a Two Worlds mandala, one common representation of the cosmos of esoteric Buddhism. All these buildings are located along a north-south axis; except for the Niō Gate, the existence--if not the depicted size and shape--of each one can be verified by archaeological findings

Buildings are also scattered to the east and west of the central axis. Most of these are fairly small, but several are significant in size: a Lecture Hall, immediately to the west of the Golden Hall, where monks would gather to hear sermons and readings of the sutras; a three-tiered pagoda to the east of the Golden Hall; and a five-bay wide structure, the Zenpōin, south of the Lecture Hall. The other buildings no doubt included monks' residences, dining quarters, and meditation chapels.

Among the structures depicted are 26 ruined buildings, marked by rows of circles that indicate their foundation stones. The ruins led Akira Seichi to argue that the painting was done after a catastrophic temple fire that occurred in 1418 (Akira 84). Of course, buildings could fall into ruin for many reasons, and a temple without substantial funding could find them hard to rebuild. In other words, although the painting shows a substantial temple complex, the ruins suggest that it was well past its days of glory. Yet Enichiji was still an important presence: notations on the painting indicate that the temple controlled the local territories of Fujikura and northern Kawanuma, both some distance away.

Archaeologists have used the painting to guide excavations of the Enichiji site, but have discovered significant differences between its contents and their findings. The pagoda, five tiers rather than three, was further to the north than it appears in the painting. There is no archaeological evidence of a building of any type immediately to the west of the Golden Hall, but a large structure that was probably the Lecture Hall is located to the north of the Golden Hall. The painting was probably not intended to be an accurate map of the temple complex, and of course the compound's layout must have changed as buildings were reconstructed and moved. Remains of a smaller structure, for instance, are found in the middle of the Lecture Hall remains. This may have been the Konpondō, a building that perhaps was constructed after the Lecture Hall was moved to another site.

The painting was restored a number of times; the first recorded instance was in 1511, according to an inscription on the back of the painting which says that the repairs took place at Mt. Kōya. Since Kōya was the spiritual headquarters of the Shingon school of Buddhism, this is evidence that Enichiji was probably affiliated with Shingon by that time. During the Edo period, the painting was restored three more times.

Why was the painting done and how might it have been used? Perhaps monks displayed it to prospective supporters to collect donations for the restoration of buildings destroyed by fire or other calamities. The ruined buildings could have served as evidence for Enichiji's past glories and its current sad state--just as the monks of other temples throughout the medieval period tugged at the heart and pursestrings of the pious.

The photograph of the painting was provided by the Fukushima Prefectural Museum. We would like to thank the museum's former Assistant Director Kaketa for helping us obtain the photograph, and for graciously arranging for Janet Goodwin to view the actual painting, which is not regularly displayed for fear of deterioriation. Information on the painting came from the following sources: Akiyama 1989, Bandai Machi Kyōiku Iinkai 1985, Bandaisan Enichiji Shiryōkan 1993. For full bibliographic references see Sources.